Most people learn at a young age that it feels good to give to others. Many people have been taught by parents, teachers, or mentors that “it is better to give than to receive.” Some people attach a moral or spiritual significance to giving. However, the act of giving itself can be quite complex, involving gray areas of agency, impact, amount, timing, manner, and cultural norms. This article explores not just how to give, but how to give well, by understanding the spirit of the gift and communicating it to the rising generation. This is intentional philanthropy: developing and understanding the why behind your charitable giving.

The Nature of Generosity

Generosity is a topic that philosophers, sages, and more recently wealth advisors, have spilled ink on. This article will use Aristotle as an approach to the topic not because he was the first or last word on the matter, but because he has a rational and balanced approach that is easy to add layers of nuance on top of. In Book IV of his Ethics, Aristotle describes what generosity looks like.[1]

“The generous person gives to the right people, and the right amount, and at the right time. Also, he or she gives with pleasure. Generosity is a quality that is relative to the wealth of an individual. The generosity of a gift does not depend on its amount, but on the attitude of the giver, and a generous attitude gives according to what it can afford. It is therefore possible that the smaller giver may be the more generous, if he or she give from smaller wealth.”

In other words, a generous person happily gives the right amount (relative to their own financial situation) to the right people (i.e., those who need assistance). In the next section of his writing, Aristotle moves on to discuss the ancient Athenian equivalent of high-net-worth philanthropy in the 21st century. He calls it “magnificence,” which literally means “to do something great.”

Magnificent Gifts

Unlike generosity, which is a relative quality, magnificence is the domain of the wealthy, who can reasonably afford to give impressive gifts. “The magnificent person is an artist in expenditure. He or she can discern what is suitable and spend great sums with good taste. And consequently, the objects he or she produces are also great and in good taste. The motive of the magnificent person in such expenditure will be the nobility of the action. Moreover, he or she will spend gladly and lavishly.”

According to Aristotle’s definition, a magnificent gift (large-scale philanthropy) is a public act that is both grand and in good taste. It is public due to its visibility and impact, and because it is meant to inspire others. Modern high-net-worth families might participate in either form of giving at different times. Some of their gifts will be generous, and some will be magnificent.

Aristotle’s definitions create a framework for us, but they raise more questions than they answer. It may be true that the generous give the right amount at the right time to the right people—what does “right” mean in practice? How does one make a magnificent and public gift “in good taste” when so many spiritual and philosophical traditions advise giving quietly and privately. In this article, we’ll flesh out what giving might look in the modern era as part of a philanthropy program that can be scaled for size. Specifically, we’ll focus on intentional philanthropy, not just as a strategy for giving to maximize impact, but also as a spirit of giving, which is as important (both for giver and receiver) as the dollar amount donated to a cause.

Reasons to Give

What are the right reasons for giving? There is no single right answer, but gaining clarity on this point will help a high-net-worth family decide how much to give and where to give. It will also help them communicate this to the rising generation, who may wonder why family elders are giving the family money away.

There are many reasons for giving. The most common might include using a Charitable Trust or Family Foundation as a tax reduction strategy, setting a good example for the rising generation, assuaging ill-defined guilt over wealth, or benefiting a cause that the family deeply cares about. Everyone benefits from a well-intentioned gift. On the other hand, philanthropy as purely tax avoidance has in the past and will in the future receive the attention of the IRS. The family will miss out on building its qualitative wealth, and funds may be wasted as organizations struggle with the lack of a true partnership or alignment of goals with the donor family. Clearly expressing the intent of the gift is important for two reasons. Unless donors clearly state the intent of their gift, subsequent generations of family (or the recipient of the gift or fund) may misinterpret the intent of the gift.

When Intent is Contested

For example, in 2002, the Robertson family filed a lawsuit against Princeton University to reclaim a $35 million gift made by their parents back in 1961. The family alleged that Princeton had violated the original intent of the gift, which was intended for the Woodrow Wilson School for Public Policy and International Affairs.

By 2008, the foundation’s assets had grown to an estimated $850 million, and the family accused Princeton of misusing a quarter of a billion dollars. Princeton argued that the foundation should serve the university’s overall needs and missions and not its own ends. The legal fees for the lawsuit surpassed $25 million, resulting in significant financial costs for both parties. This case underscores the importance of clearly stating the intent of philanthropic gifts to avoid potential controversies and misunderstandings in the future.

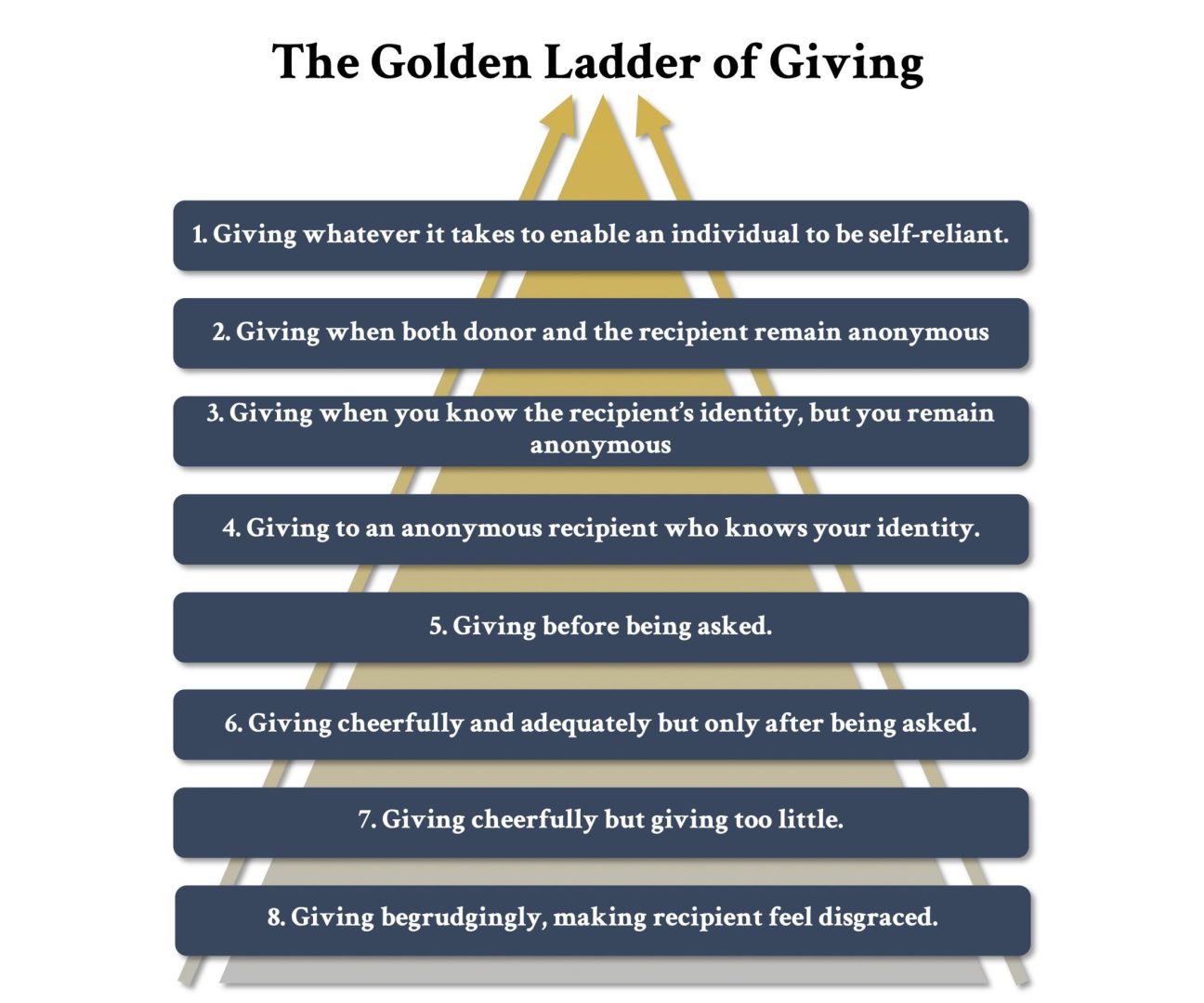

Second, giving with a vision can help build the family’s Heroic Character and Heroic Activities, two forms of qualitative Wealth. Aristotle placed generosity as virtuous middle ground between wastefulness and miserliness. He placed importance on the intention of the gift as well—the generous person enjoys giving. Likewise, most spiritual traditions place emphasis on the manner and intent of a gift as much as the gift itself. The philosopher Maimonides taught about the golden ladder of giving. An analysis of the ethical categorization of the different aspects of giving contained here could fill many pages (and is beyond the scope of this article!). Enough to say that an intention to truly help someone else, rather than to increase our social standing or out of a sense of guilt, makes the difference between giving and being generous.

Finding Inspiration

So how does a family begin finding a higher motivation for giving when it’s lacking? When people think about the positive impact they will leave when gone, they are more likely to begin to form an idea of what causes they find meaningful. Second, families can research. Perhaps they may begin by volunteering time at a local charitable organization to understand local community needs. This may open up conversations or opportunities to learn about how a financial donation can further a cause. Alternatively, there are local, national, and international databases of charitable organizations. Lastly, the family may consider a professional philanthropic consultant (either internal to the family office or a 3rd party advisors) who will guide the family through the process of helping solve the problems that matter most to them.

Generous Giving vs. Philanthropy

As we’ve already seen there is a difference between “generosity” and “magnificence” in giving. Let’s translate the distinction in modern terms: “generous giving” and “intentional philanthropy.” Generous giving is relative to the wealth of the individual situation and is often anonymous. The family directs much of this generosity towards the people and organizations they encounter in everyday life. For example, families with school-aged children donate to their private school, then perhaps a zoo that the children attend. As these children get older, the family may donate to a college, or a local arts center. Giving reflects the situations and needs directly confronting the family in the communities in which they happen to be involved. As such, these giving choices may reflect the social obligations (perhaps even direct requests to the family), rather than focus on a particular charitable passion that the family shares.

Generous giving is good, but it should have a distinct and separate place in the overall giving budget from intentional philanthropy. Families who wish to engage in intentional philanthropy and inspire others to leave a similar legacy should consider focusing their efforts and giving vision around a particular area of needs. By engaging in intentional philanthropy, the family can help ensure that it is giving the right amount to the right people and organizations.

A good philanthropic organization can make donations more effective and help ensure that the right money is being given to the right causes. Ultimately, the original impulse matters. The spirit of generosity should pervade the planning and execution of a philanthropic mission.

Summary

It is hard for families to give when they do not know their reason for giving and the impact that their giving has. By creating an intentional philanthropy strategy, families can see the impact of their charitable giving on the causes that they most care about. Additionally, when they define their intentional giving mission, they will strengthen the cohesion of the family identity.

Families should be intentional about the spirit of charitable giving in order to “give the right amount at the right time to the right people.” It is intentional gifts that will have the greatest positive impact both for the one giving and the one receiving. Lastly, families that communicate a compelling vision for intentional philanthropy to the rising generation will be more successful at leaving a legacy.

[1] N.B. The following passages have been adapted from a literal translation of Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics Book IV for brevity and clarity.