In 1973, the artist Pablo Picasso died with an estate worth $100-$250M and no estate plan. The ensuing battle over his estate lasted six years and cost $30M. This was good for lawyers and not so good for Picasso’s descendants! Unfortunately, Picasso’s estate is just one example of one of four common estate planning pitfalls.

Many people either do not have an estate plan. Or if they do have one, they do not update their estate plan to reflect assets accumulated later in life. This can create hassle and expense for heirs. Lawyer’s fees are not the only issue at stake—there are also taxes. The tax rate imposed on what are called “taxable estates” can be as high as 55% on anything over the exclusion amount. This can result in millions of dollars of avoidable estate tax. There are a range of options, from straightforward to sophisticated, to help clients maximize the amount of their estate they leave as a gift to their descendants. One doesn’t need to be a Picasso to benefit from the use of trusts in an estate plan.

A revocable living trust is the foundation of most estate plans. There are four estate planning pitfalls to avoid when creating a revocable living trust. Be sure to bring these up with your estate planning attorney in order to ensure that your trust will function properly and meet your or your client’s goals. If you are an estate planning attorney, make sure that your process avoids all four of these.

Pitfall 1: Lack of Funding

Many clients think that as soon as they sign a trust hot off the attorney’s press, they are done, will avoid probate, and have a great dispositive plan for their beneficiaries. This is the first of the estate planning pitfalls. After they sign the trust, families need to complete another vital step. The clients must “fund” the trust by titling their assets to the trust. No matter how elaborate a trust is, it is useless without assets. Only assets held in the trust will avoid probate and (if in excess of the exemption amount) estate taxes. The following story shared by one of our clients illustrates the importance of funding a trust:

The client’s mother lived in California, and her home, accounts, and other assets were all properly titled to her trust. At some point, she refinanced her home. Typically, lenders allow a refinance to close only after owners take the home out of a trust. Owners have to re-title the house to the trust after the refinance closes. However, this client’s mother neglected to re-title the home back to her trust. Unfortunately, she passed away shortly after, and the home was still titled to her individual name and subject to probate.

California is a state that has statutory attorney’s fees based on a percentage of the value of the estate subject to probate. The home’s value was over $700,000 at the time of her death. What should have been a very simple process of probating the one asset and re-titling the home to the trust ended up costing the estate $14,000 in statutory attorney’s fees. If the client’s mother had remembered (or been properly advised) to transfer her home title back to the trust after the refinance, she could have saved all of that.

Pitfall 2: Tax Code Changes

Assets within a revocable living trust can still be subject to estate tax. The revocable living trust should be used for those clients who fall within the parameters of a taxable estate. However, the estate tax exemption fluctuates significantly from decade to decade. There is no way of knowing what the estate tax exclusion amount will be when you die. The second of 4 estate planning pitfalls is a failure to anticipate tax code changes.

In the past 25 years, the estate tax exclusion amount has been as low as $600,000 in 1997. Currently it is as high as $12.06M, adjusted yearly for inflation. If Congress again fails to act before 2025, the current law sunsets. Consequently, the estate tax exclusion amount will revert back to what it was in 2017, which is a little over $5M. Therefore, proper tax planning within the revocable living trust is critical for anyone with some assets.

Portability of Unused Estate Tax Exclusion

The first tax planning technique to use is “portability”. This is a provision of the tax code first introduced in the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 that allows the surviving spouse of a decedent to make an election to “port” over the deceased’s unused estate tax exclusion amount (called the DSUE, or Deceased Spousal Unused Exclusion amount). While the surviving spouse makes this election on a properly filed IRS Form 706 (United States Estate (and Generation Skipping Transfer) Tax Return), the revocable living trust should also expressly mention this option for the surviving spouse. The obvious benefit to this technique is the doubling of the tax exemption amount for a married couple.

Disclaiming Distributions

Second, the surviving spouse can “disclaim” distributions from the deceased spouse’s share of the trust property. By exercising this disclaimer, the surviving spouse can direct all or a portion of the deceased spouse’s share to a credit shelter trust, thus preserving the deceased spouse’s estate tax exemption. The surviving spouse is typically the sole beneficiary of the credit shelter trust, and thus could enjoy the benefits of that trust property while still taking advantage of the estate tax savings.

Finally, those families with substantial wealth will want to strongly consider leaving their assets to their children and descendants in trusts which keep those assets out of their estates for potentially generations to come. This can save literally millions of dollars in taxes for future generations. In future posts, we will address these sophisticated tax strategies.

Pitfall 3: Not Doing “People Planning”

Many clients assume that their two (or more!) children can serve as joint trustees after they have passed away and believe that everyone will work together with no conflicts. This is the third of the common estate planning pitfalls–failing to do “people planning.” Unfortunately, when siblings serve as joint Trustees, they often find it difficult to navigate the trust administration without conflict. Attorneys should caution their clients against naming more than one sibling as trustee. The potential complexity of administering the trust, the emotions caused by the grantor’s death, and any latent tension in sibling dynamics can be a volatile mix that harms family dynamics for years if not generations.

There is also the problem of logistics. Trusts often require all trustees to co-sign for an action of the trustee to be effective. When there are a few trustees and they live in different areas of the country, trust administration can become delayed and inefficient. Time delays are the best-case scenario. If the Trustees do not agree on any given action, and there is no mechanism for “breaking a tie”, no action can take place. Court action may be needed to resolve the disagreement.

Furthermore, the trust may give the trustees discretion on distributions to beneficiaries. In this case the trustees may disagree on how liberal to make these distributions. The resulting strife over who gets what, when, may cause serious rifts. Note that this situation may not be a problem for families in which there are only two children who are set to receive the trust estate 50/50 outright. However, the family and their advisor should properly consider these potential issues together.

Pitfall 4: Distribution Provisions

Many clients will simply name their children as beneficiaries of their trust and leave the matter there. But it makes a big difference how the trust estate is left to children and descendants. For example, the client should consider the existing or potential number of descendants within the next two generations. The client can then determine either to leave the estate in trust to future generations per stirpes or per capita. Per stirpes leaves a percentage of the trust estate to the client’s children.

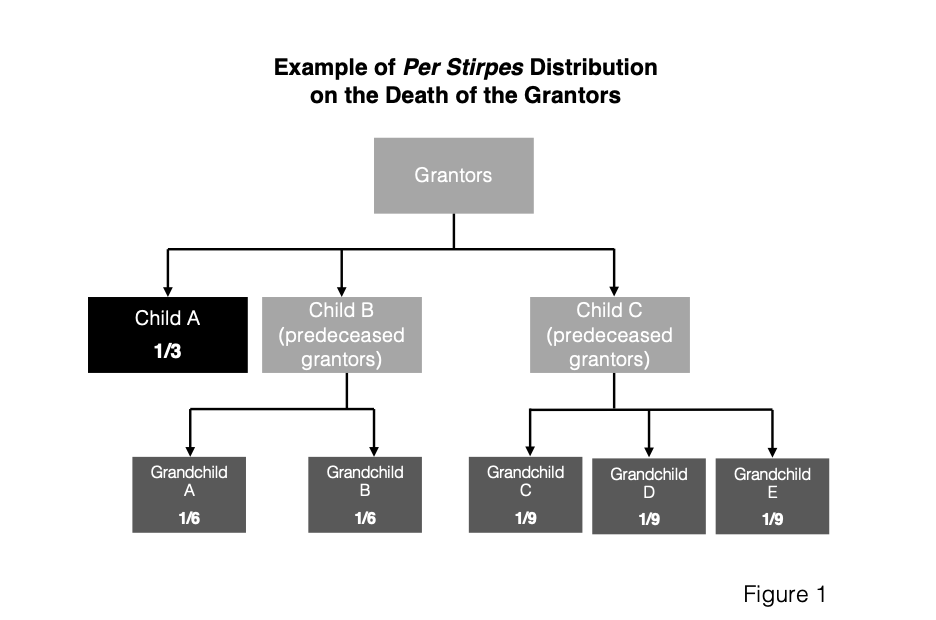

For example, a client (grantor) has three children and two of the children predecease the grantor. The two predeceased children have left two and three grandchildren, respectively. In this case the surviving child would receive 1/3 of the trust estate. The two grandchildren from one of the predeceased children would split that child’s 1/3 to receive 1/6 each. The three grandchildren from the other predeceased child would split that child’s 1/3 to receive 1/9 each (see Figure 1).

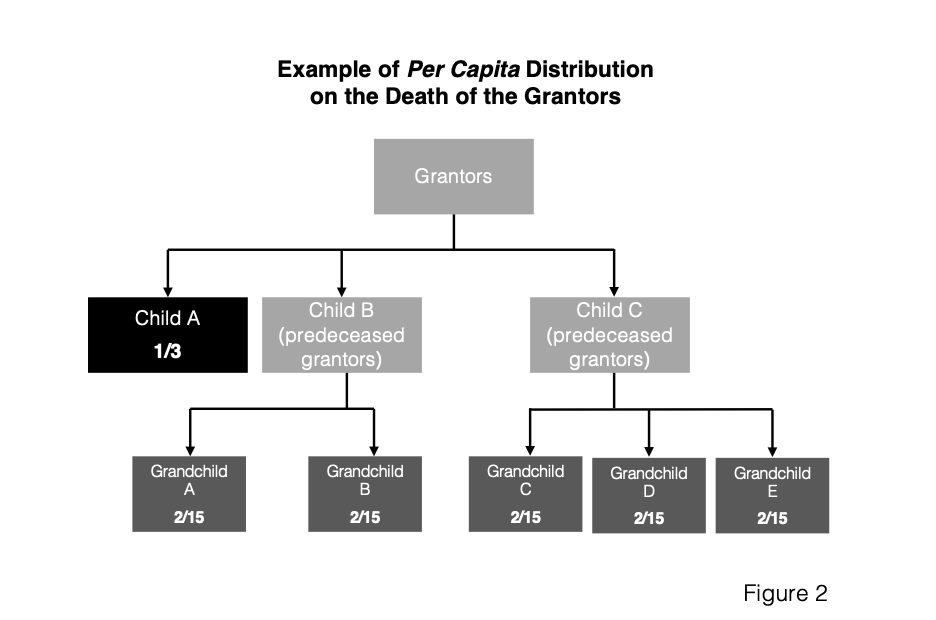

For this same example, applying per capita at each generation would generate a very different result for the grandchildren. The surviving child would still receive 1/3 of the trust estate. However, all five of the grandchildren from the two predeceased children would each receive an equal 2/15 of the trust estate. This equalizes the grandchildren’s share at that generation (see Figure 2).

Bonus: Considerations for Blended Families

How should an estate plan deal with blended families? This last point is not one of the estate planning pitfalls. However, it is an important consideration for clients and their estate planning attorneys. Sometimes one of the spouses and not the other brings significant wealth into a second marriage. Clients should understand and decide how that wealth is to be passed on. An estate planning attorney can inform clients on the options available to make assets available to a surviving spouse, and yet have those assets pass to the intended beneficiaries following the death of the second spouse.

Marital and family (bypass) trusts are an effective way to provide for a surviving spouse. Trust assets will still pass on to the descendants of the first to die. This protects those assets from a subsequent remarriage of the surviving spouse, or the surviving spouse’s children (if that is the intent of the grantors).

Lastly, clients should consider the impact that their gift may have on each beneficiary. Very often, beneficiaries of the same trust may be in very different stages of life. What may be an appropriate distribution schema for one beneficiary, may prove harmful for another.

For example, one beneficiary may be responsible and have an established career. She will responsible use her distribution (whether given to her outright or in trust) to enhance her life as intended. But she has a brother who had a rough start as a young adult and is currently struggling with a drug addiction. An outright distribution of his share of the trust estate could prove detrimental to his life, as it would allow him to fund a harmful lifestyle. In the latter case, leaving the brother’s share in trust with a conservative distribution standard may motivate him to pursue recovery. The trust may also give the trustee guidance on making use of trust funds for rehabilitation and incentives for improving his life. In summary, grantors should not assume one-size-fits-all distribution standards if the needs and lifestyles of their beneficiaries are very different.

Summary

The revocable living trust is an excellent tool for foundational estate. When meeting with a trust and estates attorney, clients should be sure to avoid the four common estate planning pitfalls. Be sure to discuss the following: 1) the trust has been funded, 2) tax code changes have been anticipated, 3) family dynamics have been managed, and 4) implications of distribution provisions have been considered.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this post is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.